General History

With the growing United States involvement in the Vietnam War, Rangers were again called to serve their country. The 75th Infantry was reorganized once more on January 1, 1969, as a parent regiment under the Combat Arms Regimental System. Fifteen separate Ranger companies were formed from this reorganization. Thirteen served proudly in Vietnam until inactivation on August 15, 1972.

Ranger companies, consisting of highly motivated volunteers, served with distinction in Vietnam from the Mekong Delta to the Demilitarized Zone. Assigned to independent brigade, division, and field force units, they conducted long-range reconnaissance and exploitation operations into enemy-held and denied areas, providing valuable combat intelligence.

The companies assumed the assets of the long-range patrol units, some of which had been in existence in Vietnam since 1967. They served until the withdrawal of American troops. An Indiana National Guard Unit, Company D, 151st Infantry (Ranger), also experienced combat in Vietnam.

At the end of the war in Vietnam, Ranger companies were deactivated, and their members were dispersed among the various units of the Army. Many men went to the 82nd Airborne Division at Fort Bragg, North Carolina. However, two long-range reconnaissance patrol units were retained in the force structure. Transferred to the Army National Guard (D/151st, Indiana and G/143rd, Texas), they were designated as Infantry Airborne Ranger Companies.

This history deals with the activities, personnel and accomplishments of the 75th Infantry (Ranger), Regiment companies during the period 1 February 1969 through 15 October 1974 and makes reference to the units who preceded the designation of the 75th Infantry (Ranger).

Throughout history, the need for a small, highly trained, far ranging unit to perform reconnaissance surveillance, target acquisition, and special type combat missions has been readily apparent. In Vietnam this need was met by instituting a Long Range patrol program to provide each major combat unit with this special capability. Rather than create an entirely new unit designation for such an elite force, the Department of the Army looked to its rich and varied heritage and on 1 February 1969 designated the 75th Infantry Regiment; the present successor to the famous 5307th Composite Unit (MERRILL’S MARAUDERS), as the parent organization for an Department of the Army designated Long Range patrol (LRP) units, and the parenthetical designation (RANGER) in lieu of (LRP) for these units. As a result, the Long Range Patrol Companies and Detachments (LRP): formally the Long Range Reconnaissance Patrol (LRRP) (Provisional) assigned to the major army commands in the Republic of Vietnam became the 75th Infantry (Ranger) Regiment.

Soon after arriving in Vietnam the commanders of the Divisions and separate Brigades realized the need for an elite reconnaissance element to provide the combat intelligence needed to accomplish the mission of finding a very elusive enemy that fought a sustained battle when, and where they chose.

The Department of the Army had authorized a Company size reconnaissance element at Corp level throughout the US Army but the personnel and equipment had never been assigned to the Corp level command. In fact the only Corp level reconnaissance elements that existed were the V Corps and VII Corps Long Range Reconnaissance companies that were stationed in Germany. These units had the primary mission of a stay behind force that would provide the Corps level command with the intelligence needed after the allied forces had withdrawn from West Germany. The reconnaissance teams would report on enemy troop movements and tactical deployment of the enemy forces.

With the advent of the Vietnam war escalation, each Division and Separate Brigade stationed in the Republic of Vietnam (RVN) formed a Long Range Reconnaissance Patrol (Provisional) unit known as the LRRP. Many variations of organizational makeup characterized this ad hoc form of a provisional unit. Each brigade commander organized the LRRP to suit the needs of his command and the Tactical Area Of Operational Responsibility (TAOR). Command and Control was decentralized and given to the Brigade commanders who asked for volunteers from the infantry units assigned to the brigade.

These units lacked peace time schooling and had no Department of the Army approved Table of Organization and Equipment (TO&E). The leaders were the officers and non commissioned officers who previously had attended the RANGER course or the RECONDO schools of the 1O1st Airborne Division and 82nd Airborne Division or the Jungle Operations Center in Panama. These units were functional for the period of May 1965 through December 1967. In December 1967 the Department of me Army authorized the formation of the Long Range Patrol (LRP) companies and detachments who absorbed the personnel of the previously unauthorized Long Range Reconnaissance Patrol (Prov) units.

UNIT MAJOR COMMAND

Co. D, 17th Infantry, (LRP) V Corps Federal Republic of Germany

Co. C, 58th Infantry (LRP) VII Corps Federal Republic of Germany

Co. E, 20th Infantry (LRP) I Field Force Vietnam

Co. F, 51st Infantry (LRP) II Field Force Vietnam

Co. D, 151st Infantry (LRP) II Field Force Vietnam

Co. E, 50th Infantry (LRP) 9th Infantry Division

Co. F, 50th Infantry (LRP) 25th Infantry Division

Co. E, 51st Infantry (LRP) 23rd Infantry Division

Co. E, 52d Infantry (LRP) 1st Cavalry Division

Co. F, 52nd Infantry (LRP) 1st Infantry Division

Co. E, 58th Infantry (LRP) 4th Infantry Division

Co. F, 58th Infantry (LRP) 1O1st Airborne Division

71st Infantry Detachment (LRP) 199th Infantry Brigade

74th Infantry Detachment (LRP) 173rd Airborne Brigade

78th Infantry Detachment (LRP) 3rd Brigade, 82nd Airborne Division

79th Infantry Detachment (LRP) 1st Brigade, 5th Mechanized Division

These units continued to operate throughout the 4 Military Regions of the Republic of Vietnam providing the major commands with the intelligence needed to find the enemy and disrupt his line of communication and supply. The mission designator of “Reconnaissance” was dropped as these units performed not only reconnaissance type missions but also combat missions such as ambush, prisoner snatch and raids.

Each individual unit conducted their own training and indoctrination classes. On 1 February 1969 the above units became 75th Infantry (Ranger) companies except for Co. D, l5lst Infantry (LRP) of the Indiana National Guard which only dropped the (LRP) designation but added the (Ranger) designation. Department of the Army ordered that the above shown units would now be designated as shown below.

UNIT MAJOR COMMAND PERIOD OF SERVICE

Co A (Ranger),75th Infantry Ft Benning / Ft Hood 1 Feb. 1969 – 15 Oct. 1974

Co B (Ranger),75th Infantry Ft Carson / Ft Lewis 1 Feb. 1969 – 15 Oct. 1974

Co C (Ranger),75th Infantry I Field Force Vietnam 1 Feb. 1969 – 25 Oct. 1971

Co D (Ranger),151st Infantry II Field Force Vietnam 1 Feb. 1969 – 20 Nov. 1969

Co D (Ranger),75th Infantry II Field Force Vietnam 20 Nov. 1969 – 10 Apr. 1970

Co E (Ranger),75th Infantry 9th Infantry Division 1 Feb. 1969 – 12 Oct. 1970

Co F (Ranger),75th Infantry 25th Infantry Division 1 Feb. 1969 – 15 Mar 1971

Co G (Ranger),75th Infantry 23rd Infantry Division 1 Feb. 1969 – 1 Oct. 1971

Co H (Ranger),75th Infantry 1st Cavalry Division 1 Feb. 1969 – 15 Aug. 1972

Co I (Ranger),75th Infantry 1st Infantry Division 1 Feb. 1969 – 7 Apr. 1970

Co K (Ranger),75th Infantry 4th Infantry Division 1 Feb. 1969 – 10 Dec. 1970

Co L (Ranger),75th Infantry 1O1st Airmobile Division 1 Feb. 1969 – 25 Dec. 1971

Co M (Ranger),75th Infantry 199th Infantry Brigade 1 Feb. 1969 – 12 Oct. 1970

Co N (Ranger),75th Infantry 173rd Airborne Brigade 1 Feb. 1969 – 25 Aug. 1971

Co 0 (Ranger),75th Infantry 3rd Brigade,82nd Abn. 1 Feb. 1969 – Division 20 Nov. 1969

Co P (Ranger),75th Infantry 1st Brigade, 5th Mech. 1 Feb. 1969 – Division 31 Aug. 1971

The above Ranger companies of the 75th Infantry conducted combat Ranger missions and operations for three years and seven months, every day of the year while in Vietnam, and companies A,B, and 0 performed Ranger missions state side for five years and eight months. Like the original unit from whence their lineage as Neo Marauders was drawn, 75th Rangers came from the Infantry, Artillery, Engineers, Signal Medical Military Police, Food Service, Parachute Riggers and other Army units. They were joined by former adversaries, the Vietcong and North Vietnamese Army soldiers who became “Kit Carson Scouts” and fought alongside the Rangers against their former units and comrades.

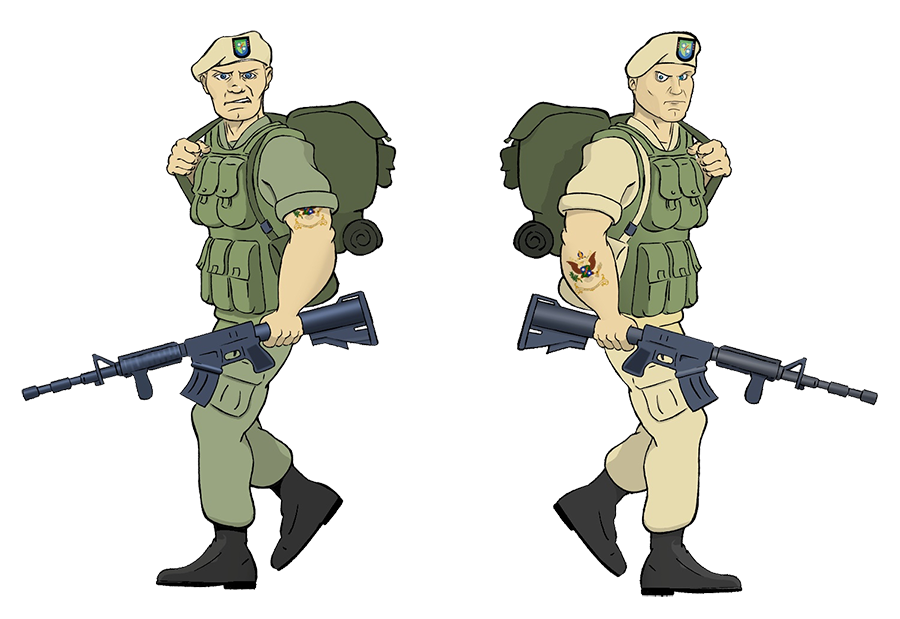

Unlike Rangers of other eras in the 20th century who trained in the United States or in friendly nations overseas, Rangers in Vietnam were activated, trained and fought in the same geographical areas, a high speed approach to training. Training was a combat mission for volunteers. Volunteers were assigned and not accepted in the various Ranger companies until after a series of patrols by which the volunteer had passed the acid test of a Ranger, combat, and was accepted by his peers. Following peer acceptance, the volunteer was allowed to wear the black beret and red, white and black scroll shoulder sleeve insignia bearing his Ranger company identity. All Ranger companies were authorized parachute pay.

Modus operandi for patrol insertion varied, however the helicopter was the primary means for insertion and ex-filtration of enemy rear areas. Other methods included foot, wheeled, tracked vehicles, airboats, Navy swift boats, and stay behind missions where the Rangers stayed in place as a larger tactical unit withdrew. False insertions by helicopter was a means of security from ever present enemy trail watchers. General missions consisted of locating the enemy bases and lines of communication. Special missions included wiretap, prisoner snatch, Platoon and Company size Raid missions and Bomb Damage Assessments (BDA’s) following B-52 Arc Light missions as well as the ambush mission that was common after the Ranger team had performed its primary mission.

Staffed principally by graduates of the US Army Ranger School Paratroopers and Special Forces trained men, the bulk of the Ranger volunteers came from the soldiers who had no chance to attend the school, but carried the fight to the enemy. Rangers in the grade of E-4 to E-6 controlled fires from the USS New Jersey’s 16 inch guns in addition to helicopter gun ships, piston engine and high performance aircraft while frequently operating far beyond conventional artillery and infiltrated enemy base camps, capturing prisoners or conducting other covert operations. The six man Ranger team was standard and a twelve man team was used for combat patrols in most instances, however some units operated occasionally in two man teams in order to accomplish the mission.

The Vietnam Rangers of the 75th Infantry were awarded the title of Neo Marauders by the Secretary of the Army, Stanley Resor, for having lived up to the standards set by the original Marauders during World War II. Army Chief of Staff Creighton Abrams who observed the 75th Ranger operations in Vietnam as commander for all US forces there, selected the 75th Rangers as the role model for the first US Army Ranger units formed in peacetime in the history of the United States Army. Today, the modern Rangers of the 75th Ranger Regiment continue the tradition of being the premier fighting element of the active army. The traditions and dedication to their fellow RANGERS continues!!

75th INFANTRY (RANGER) REGIMENT, VIETNAM ENTITLEMENTS

Campaign Streamers, Vietnam

Counteroffensive Phase VI

Tet 69 Counteroffensive

Summer- Fall 1969

Winter- Spring 1969

Sanctuary Counteroffensive

Counteroffensive Phase VII

Consolidation I

Consolidation II

Cease Fire

Decorations, Vietnam

RVN Gallantry Cross w/Palm – 23 Awards

RVN Civil Actions Honor Medal – 10 Awards

US Valorous Unit Award – 6 Awards

US Meritorious Unit Commendation – 2 Awards

Medal of Honor

Ranger Recipients of the Medal of Honor

Robert D. Law *

Gary L. Littrell

Robert J. Pruden *

Lazlo Rabel *

* Posthumously Awarded

The Medal of Honor is the highest military medal awarded by the United States. The individuals presented here as recipients served in a unit contributing to the lineage of the 75th Ranger Regiment.

*LAW, ROBERT D.

Rank and organization: Specialist Fourth Class, U.S. Army, Company I (Ranger), 75th Infantry, 1st Infantry Division.

Place and date: Tinh phuoc Thanh province, Republic of Vietnam, 22 February 1969

Entered service at: Dallas, TX

Born: 15 September 1944, Fort Worth, TX

Citation: For conspicuous gallantry and intrepidity in action at the risk of his life above and beyond the call of duty. Sp4c. Law distinguished himself while serving with Company 1. While on a long-range reconnaissance patrol in Tinh phuoc Thanh province, Sp4c. Law and 5 comrades made contact with a small enemy patrol. As the opposing elements exchanged intense fire, he maneuvered to a perilously exposed position flanking his comrades and began placing suppressive fire on the hostile troops. Although his team was hindered by a low supply of ammunition and suffered from an unidentified irritating gas in the air, Sp4c. Law’s spirited defense and challenging counterassault rallied his fellow soldiers against the well-equipped hostile troops. When an enemy grenade landed in his team’s position, Sp4c. Law, instead of diving into the safety of a stream behind him, threw himself on the grenade to save the lives of his comrades. Sp4c. Law’s extraordinary courage and profound concern for his fellow soldiers were in keeping with the highest traditions of the military service and reflect great credit on himself, his unit, and the U.S. Army.

Littrell, Gary Lee

Rank and organization: Sergeant First Class, U.S. Army, Advisory Team 21, 11 Corps Advisory Group.

Place and date: Kontum province, Republic of Vietnam, 4-8 April 1970

Entered service at: Los Angeles, CA

Born: 26 October 1944, Henderson, KY

Citation: For conspicuous gallantry and intrepidity in action at the risk of his life above and beyond the call of duty. Sfc. Littrell, U.S. Military Assistance Command, Vietnam, Advisory Team 21, distinguished himself while serving as a Light Weapons Infantry Advisor with the 23d Battalion, 2d Ranger Group, Republic of Vietnam Army, near Dak Seang. After establishing a defensive perimeter on a hill on April 4, the battalion was subjected to an intense enemy mortar attack which killed the Vietnamese commander, 1 advisor, and seriously wounded all the advisors except Sfc. Littrell. During the ensuing 4 days, Sfc Littrell exhibited near superhuman endurance as he single-handedly bolstered the besieged battalion. Repeatedly abandoning positions of relative safety, he directed artillery and air support by day and marked the unit’s location by night, despite the heavy, concentrated enemy fire. His dauntless will instilled in the men of the 23d Battalion a deep desire to resist. Assault after assault was repulsed as the battalion responded to the extraordinary leadership and personal example exhibited by Sfc. Littrell as he continuously moved to those points most seriously threatened by the enemy, redistributed ammunition, strengthened faltering defenses, cared for the wounded and shouted encouragement to the Vietnamese in their own language. When the beleaguered battalion was finally ordered to withdraw, numerous ambushes were encountered. Sfc. Littrell repeatedly prevented widespread disorder by directing air strikes to within 50 meters of their position. Through his indomitable courage and complete disregard for his safety, he averted excessive loss of life and injury to the members of the battalion. The sustained extraordinary courage and selflessness displayed by Sfc. Littrell over an extended period of time were in keeping with the highest traditions of the military service and reflect great credit on him and the U.S. Army.

*Pruden, Robert J.

Rank and organization: Staff Sergeant, U.S. Army, 75th Infantry, Americal Division.

Place and date: Quang Ngai Province, Republic of Vietnam, 29 November 1969

Entered service at: Minneapolis, MN

Born: 9 September 1949, St. Paul, MN

Citation: For conspicuous gallantry and intrepidity in action at the risk of his life above and beyond the call of duty. S/Sgt. Pruden, Company G, distinguished himself while serving as a reconnaissance team leader during an ambush mission. The 6-man team was inserted by helicopter into enemy controlled territory to establish an ambush position and to obtain information concerning enemy movements. As the team moved into the preplanned area, S/Sgt. Pruden deployed his men into 2 groups on the opposite sides of a well used trail. As the groups were establishing their defensive positions, 1 member of the team was trapped in the open by the heavy fire from an enemy squad. Realizing that the ambush position had been compromised, S/Sgt. Pruden directed his team to open fire on the enemy force. Immediately, the team came under heavy fire from a second enemy element. S/Sgt. Pruden, with full knowledge of the extreme danger involved, left his concealed position and, firing as he ran, advanced toward the enemy to draw the hostile fire. He was seriously wounded twice but continued his attack until he fell for a third time, in front of the enemy positions. S/Sgt. Pruden’s actions resulted in several enemy casualties and withdrawal of the remaining enemy force. Although grievously wounded, he directed his men into defensive positions and called for evacuation helicopters, which safely withdrew the members of the team. S/Sgt. Pruden’s outstanding courage, selfless concern for the welfare of his men, and intrepidity in action at the cost of his life were in keeping with the highest traditions of the military service and reflect great credit upon himself, his unit, and the U.S. Army.

*Rabel, Laszlo

Rank and organization: Rank and organization: Staff Sergeant, U.S. Army, 74th Infantry Detachment (Long Range Patrol), 173d Airborne Brigade.

Place and date: Binh Dinh Province, Republic of Vietnam, 13 November 1968

Entered service at: Minneapolis, MN

Born: 21 September 1939, Budapest, Hungary

Citation: For conspicuous gallantry and intrepidity in action at the risk of his life above and beyond the call of duty. S/Sgt. Rabel distinguished himself while serving as leader of Team Delta, 74th Infantry Detachment. At 1000 hours on this date, Team Delta was in a defensive perimeter conducting reconnaissance of enemy trail networks when a member of the team detected enemy movement to the front. As S/Sgt. Rabel and a comrade prepared to clear the area, he heard an incoming grenade as it landed in the midst of the team’s perimeter. With complete disregard for his life, S/Sgt. Rabel threw himself on the grenade and, covering it with his body, received the complete impact of the immediate explosion. Through his indomitable courage, complete disregard for his safety and profound concern for his fellow soldiers, S/Sgt. Rabel averted the loss of life and injury to the other members of Team Delta. By his gallantry at the cost of his life in the highest traditions of the military service, S/Sgt. Rabel has reflected great credit upon himself, his unit, and the U.S. Army.

The established criteria follows:

a. The Medal of Honor [Army], section 3741, title 10, United States Code (10 USC 3741), was established by Joint Resolution of Congress, 12 July 1862 (amended by acts 9 July 1918 and 25 July 1963).

b. The Medal of Honor is awarded by the President in the name of Congress to a person who, while a member of the Army, distinguishes himself or herself conspicuously by gallantry and intrepidity at the risk of his life or her life above and beyond the call of duty while engaged in an action against an enemy of the United States; while engaged in military operations involving conflict with an opposing foreign force; or while serving with friendly foreign forces engaged in an armed conflict against an opposing armed force in which the United States is not a belligerent party. The deed performed must have been one of personal bravery or self-sacrifice so conspicuous as to clearly distinguish the individual above his comrades and must have involved risk of life. Incontestable proof of the performance of the service will be exacted and each recommendation for the award of this decoration will be considered on the standard of extraordinary merit.

From chapter 3-6, Army Regulation 600-8-22 (Military Awards) dated 25 February 1995.

Unit Histories

Courtesy of the respective Unit Historians:

A/75 & D/17 LRP & V Corps LRRP

Company A (RANGER), 75th Infantry

The Company D Long Range Patrol (Airborne), 17th Infantry formally V Corps (ABN) LRRP Co. (provisional) which was activated at 7th Army in Germany on 15 July, 1961 eventually became Company A (Airborne Ranger), 75th Infantry. The V Corps (ABN) LRRP Co. was the first of two (2) LRRP Companies authorized at Army level and was activated at 7th Army in Germany on 15 July, 1961, and was formed at Wildflecken. Major Reese Jones was the first commanding officer and Gilberto M. Martinez was the First Sergeant.

The Company was initially designated the 3779 Recon Patrol Co, (Provisional) and came under the Headquarters, 14th Armored Cavalry at Fulda, Germany (APO 26 US Forces) for administration and court martial jurisdiction. In January 1963, the Company moved to Edwards Kaserne in Frankfurt with Captain William Guinn assuming command from Major Edward Porter. On 9 May, 1963, the Company moved to Gibbs Kaseme in Frankfurt and became part of the V Corps Special Troops (Provisional) working directly for the Corps G-2. Under Captain Guinn’s leadership the V Corps LRRPs developed and perfected aspects of Long Range Patrol operations that are still in use today. Many of these ideals were incorporated into the first long range Reconnaissance Company field manual (FM31-16).

On 15 May, 1965 the Company was deactivated and re-designated as Company D, Long Range Patrol (ABN) 17th Infantry, maintaining the same mission and remaining at Gibbs Kaserne in Frankfurt, Germany. The V Corps being across the Hessian and Bavarian front north of the Main River faced four of the six most likely Soviet penetration corridors into Germany. The Company missions encompassed extensive practiced combat patrolling missions in the Bad Heisfeld – Giessen, Fulda-Hanau, Bad Kissingen — Wurzburg and Coburg – Bamberg corridors to include rehearsed deep penetration missions against Thuringian targets that were typified by the Soviet Weimar – Nobra air installation and Army facilities around Ohrdruf and Jena. The Company would be used also for special missions of infiltration that included team placement of T-4 Atomic Demolition Munitions and locating enemy battlefield targets for Army tactical nuclear delivery systems.

In 1968, the Army began a massive pullout from Europe code — named Operation REFORGER (Redeployment of Forces Germany) and Company D (LRP), 17th Infantry relocated to Fort Benning, Georgia with Captain Harry W. Nieubar the Company commander. Then on 21 February 1969, Company D (LRP) 17th Infantry became Company A (Airborne Ranger) 75th Infantry activated at Fort Benning, Georgia under Captain Thomas P. Meyer. The Company kept its REFORGER mission in case of war in Europe. This was one reason that the Company never deployed to Vietnam. While at Fort Benning, Georgia Company A performed such duties as supporting the ranger patrolling committee. The Commander of the 197th Infantry Brigade Col. Willard Latham put the Company in charge of the “Drug Rehabilitation Program” for soldiers with drug problems and put them through rehabilitation cycles and helped reconditioned them with training and hard labor chores.

On 3 February, 1970, Company A (Ranger) 75th Infantry, arrived at Fort Hood, Texas from Fort Benning, Georgia under the command of Captain Johnathan Henkel and was assigned to the 1st Armored Division. Until June 1972, the primary mission of Company A (Ranger) 75th Infantry was to support Project MASSTER (Mobile Army Sensor Systems Test, Evaluation, and Review). This work was difficult and unglorious and involved the constant testing of surveillance, target acquisition, seismic intrusion detectors and night observation equipment which paved the way and benefited the Army in it’s performance in the Gulf War twenty years later. The mission changed again in July 1972, to provide a Long Range reconnaissance capability for the 1st Cavalry Division and stay in a high state of training for REFORGER.

On 8 January, 1973, Captain Raymond D. Nolen assumed command of Company A (Ranger) 75th Infantry. Over 80% of the men of Company A were Vietnam Veterans, Their First Sergeant was Walter Vick while at Fort Hood. During October 1974, the 1st Battalion (Ranger) of the 75th Infantry was activated at Fort Stewart using the assets of inactivated Ranger Company A, but it was assigned the heritage of the Vietnam Field Force Rangers of Company C. First Sergeant Bonifacio M. Romo was 1st Sgt. of A Co. 1st Ranger Battalion.

Today, the modern Rangers of the 75th Ranger Regiment continue the traditions of being the premier fighting element of the active Army. The traditions and dedication to their fellow Rangers continues.

BDQ, RVN Ranger Advisors

Advisors to ARVN Rangers

(Bit D™ng Qu‰n)

During 1951, the US Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) suggested to General De Lattre (Jean de Lattre de Tassigny – Commander in chief Indochina) that the French should form “counter-guerilla” warfare groups to operate in Vietminh – controlled areas. The French command rejected the concept of unconventional warfare units, although they did establish a Commando School at Nha Trang. By 1956, the US Advisory Group would turn this facility into a physical training and ranger-type school.

As the seriousness of the insurgency became more apparent during the early weeks of 1960, American and South Vietnamese leaders began to consider what measures might be adopted to deal with the deteriorating security situation. President of the Republic of Vietnam, Ngo Dinh Diem had his own solution. On 16 February 1960, without consulting his American military advisors, he ordered commanders of divisions and military regions to form ranger companies from the army, the reserves, retired army personnel and the Civil Guard.

In the Beginning

Activated in 1960, Army of the Republic of Vietnam (ARVN) Rangers (Bit D™ng Qu‰n [BDQ]) initially organized into separate companies to counter the guerilla war then being waged by the Viet Cong (VC). From the beginning, American Rangers were assigned as advisors, initially as members of Mobile Training Teams (MTTs), deployed from the U.S., at training centers, and later at the unit level. A small number of promising Vietnamese Ranger leaders were selected to attend the U.S. Army Ranger school at Fort Benning. As a result of their common experiences, lasting bonds of mutual respect were formed between the combat veterans of both nations. During the early days, Ranger missions focused on raids and ambushes into such VC zones as War Zone D, Duong Minh Chau, Do Xa and Boi Loi (later to be called the “Hobo Woods” by the American forces) to destroy the VC infrastructure. The well-known shoulder insignia, bearing a star and a Black Panther’s head, symbolized the courageous fighting spirit of the Vietnamese Rangers.

Training

Ranger courses were established at three training sites in May 1960: Da Nang, Nha Trang, and Song Mao. The original Nha Trang Training course relocated to Duc My in 1961 and would become the central Ranger-Bit D™ng Qu‰n-Company and Battalion sized unit training was later established at Trung Lap; to ensure a consistently high level of combat readiness, BDQ units regularly rotated through both RTC’s. Graduates of the school earned the coveted Ranger badge with its distinctive crossed swords. Ranger Training Centers conducted tough realistic training that enabled graduates to accomplish the challenging missions assigned to Ranger units. Known as the ‘steel refinery ‘ of the ARVN, the centers conducted training in both jungle and mountain warfare.

South Vietnamese combat reconnaissance was a responsibility of the Ranger Training Command and ARVN reconnaissance units and teams were trained at either the Duc My RTC Long Range Reconnaissance Patrol (LRRP) course or at the Australian-sponsored Long Range Patrol (LRP) course of the Van Kiep National Training Center; graduates were awarded the Reconnaissance Qualification badge (a pair of winged hands holding silver binoculars).

Operations

In 1962, BDQ companies were grouped to form Special Battalions: the 10th in Da Nang, the 20th in Pleiku, and the 30th Battalion in Saigon. These Special Battalions operated deep inside the enemy controlled regions on “Search and Destroy” missions. By 1963 the war expanded as main force North Vietnamese Army (NVA) units began invading the South, launching battalion and regimental-size attacks against ARVN units. To cope with the escalation by the Communists, Ranger units were organized into battalions and their mission evolved from counter-insurgency to light infantry operations. During the years 1964-66, the Ranger battalions intercepted, engaged and defeated main force enemy units. During July 1966, the battalions were formed into task forces, and five Ranger Group headquarters were created to provide command and control for tactical operations. This afforded the Rangers better control and the ability to mass forces quickly and strike more rapidly. ARVN combat divisions as well as Regional and Popular Force (RF/PF) units had a territorial security orientation that tied them to a limited geographic area. Ranger units assumed the responsibility of providing the primary ARVN mobile reaction force in each Tactical Zone; a far larger geographical operating area.

When the VC and NVA forces opened the 1968 Tet Offensive in the major cities of Vietnam, the maroon beret soldiers were rushed to the scene and were an active force in defeating the Communist threat. The 3d and 5th Ranger Groups defended and secured the capitol, Saigon and the 37th Battalion fought alongside the U.S. Marines at Khe Sanh. Rangers continued to distinguish themselves on battlefields throughout Vietnam as well as the 1970 incursion into Cambodia and Operation “Lam Son 719” in Laos. As American ground forces reduced their tactical role and began to withdraw from Vietnam, an additional mission was assumed by the BDQ. On 22 May 1970, the Civilian Irregular Defense Group (CIDG), formerly under the operational control of 5th U.S. Special Forces Group, integrated into Ranger forces, along with responsibility for border defense. With the conversion of CIDG camps to combat battalions, Ranger forces more than doubled in size.

When the NVA launched major attacks on three fronts on Easter Sunday of 1972 in an all-out effort to gain a decisive military victory Ranger units once again answered the call to defend the fatherland. Near the DMZ in Quang Tri Province, Rangers, together with ARVN, Marine and Regional Forces units, stopped the enemy after a 22-day fight in which 131 NVA tanks were destroyed and approximately 7,000 NVA soldiers were killed. At An Loc, Ranger, ARVN and Regional Force units stopped four NVA Divisions, reinforced with armor and artillery in what was probably one of the bloodiest battles of the Vietnam War. In Kontum Province, the Rangers participated in the battle of Tay Nguyen, in which still another multi-division NVA attack was smashed. At the time of the “cease-fire,” 28 January 1973, Ranger High Command estimated that the Rangers had killed 40,000 of the enemy, captured 7,000 and assisted 255 to rally to the government side. It was also reported that 1,467 crew-served weapons and 10,941 individual weapons had been captured. Of course, there was no true cease-fire, and the war continued. In 1973, the role of the Ranger Advisor was curtailed. As individual advisors rotated back to the United States, they were not replaced. Finally, by the end of 1973 the last Ranger Advisor was quietly ordered home.

During 1973, 1974 and 1975, the Rangers continued to be employed in a variety of critical combat roles, performing intelligence and reconnaissance missions and providing the ARVN with a quick reaction force. In addition, their mission of border security continued. In the last days of the war, the BDQ fought to the end, units totally destroyed in battles from the North to Saigon, many of the Ranger units fought back independently against orders – refusing to surrender – bloodying the advancing Communist forces. In Tay Ninh province the Rangers fought until Saigon fell. In Saigon, Rangers fought until the morning of 30 April when they were ordered to lay down their arms.

When the war finally ended with the fall of Saigon in 1975, most of the Ranger leaders were considered too dangerous by the communist government, and sentenced to long periods of incarceration in the dreaded “reeducation camps.” As an example, General Do ke Giai, the last commander of Ranger forces spent more than 17 years imprisonment for his fervent anti-Communist resistance.

The Role of the Advisor

The experiences of the American advisors (and a few Australians) to the BDQ were unique from other advisors and definitely different from their U.S. unit counterparts. Their mission and the force structure of the units they advised demanded more experienced and thoroughly trained individuals. Officers were almost all Ranger qualified, and after 1966 most were on a second or subsequent combat tour. The Non-Commissioned Officers were arguably the most talented Sergeants that the Army had to offer. Many of these Sergeants were experienced cadre from the Ranger Department at the Infantry School, or experienced small unit leaders with Infantry, Special Forces or Marine backgrounds; some had fought in World War II and / or Korea. It was fairly common for the more senior NCOs to serve as Ranger advisors between tours at one of the Ranger Training Camps.

According to the Military Assistance Command-Vietnam Joint manpower authorization documents, advisory teams were fairly robust. Each was authorized eight personnel to perform the support mission. The authorized grades for the Ranger battalion and group Senior Advisor were Major and Lieutenant Colonel respectively. This was usually not the case however, as a battalion advisor team routinely consisted of an experienced Captain, a Lieutenant, two NCOs and a RadioTelephone Operator (RTO). It was not uncommon to field teams of two or three personnel. The Ranger Group Headquarters advisor team was comprised of a Major, one or two Captains, two or three NCO’s, and an RTO. Living and military operations experience for the Ranger advisor varied dramatically from area to area, unit to unit, and year to year. Operations were normally conducted by Ranger battalions, but were often smaller in some locales. Frequently, multi-battalion operations were conducted under the command and control of the Ranger Group headquarters. In addition to being selected for tactical and technical proficiency, many Ranger advisors were graduates of the Military Assistance and Training Advisory Course (MATA) and Vietnamese Language School. However, the tactical requirements always exceeded the number of school slots, and most advisors depended upon lessons learned the hard way, and the good luck to have a Vietnamese counterpart who understood English. Each team was authorized a local interpreter / translator, however these proved to be of varied skills and reliability.

The primary mission of an advisor was to counsel his Vietnamese counterpart on development and implementation of operational plans as well as the tactical execution of military operations. The advisor coordinated any available combat support from U.S. forces such as artillery, armored vehicles, air strikes, helicopter gunships, naval gunfire, and medical evacuation. Additionally, the advisor was expected to escort and directly communicate with a variety of specialist teams that might accompany the unit on operations, such as artillery forward observers, Air Force forward air controllers (FAC), naval gunfire teams, canine handlers, or combat correspondents.

While differences were evident from team to team, the Ranger advisors led a unique life under an unusual set of circumstances. The highly mobile advisory team was with the Vietnamese unit at all times when it was in the field on military operations, which could last for days or weeks. Living conditions were Spartan and arduous. Frequent and intense combat was the rule for Ranger units. The team survived on limited supplies and rations (resupply in the field was sporadic at best), often with a limited knowledge of the operational plan and enemy intelligence situation. The team’s communications lifeline and link was often a single PRC-25 tactical radio. Despite, or because of these circumstances and conditions, the Ranger advisors became very adept at accomplishing their responsibilities and fulfilling their missions.

Awards and Honors

Vietnamese Ranger units and individual soldiers received a wide range of awards for valor and heroism from both the Republic of Vietnam and the United States. The 42nd and 44th Battalions were awarded their country’s National Order Fourragere, the 43rd Battalion the Military Order Fourragere, and the 21st, 37th, 41st and 52nd Battalions the Gallantry Cross Fourragere. Twenty-three Ranger units were awarded the Vietnamese Gallantry Cross with Palm unit award, with the 42nd Battalion receiving the award seven times, the 44th Battalion six times, and the 1st Group and 43rd Battalion each four times. Eleven U.S. Presidential Unit Citations (PUC) were awarded to Vietnamese Ranger units. The 37th Battalion three times, the 39th and 42d twice, and the 1st Ranger Task Force, 21st, 44th and 52nd Battalions each received the PUC once. The U.S. Valorous Unit Award was awarded to the 21st, 32d, 41st, 43d, 77th and 91st Ranger Battalions. Large numbers of individual Vietnamese Rangers were presented U.S. awards such as the Silver Star, Bronze Star, and Army Commendation Medals for acts of valor in the face of enemy forces.

A number of American Ranger Advisors were decorated for gallantry under fire, the best known is SFC Gary Lattrell, an advisor to the 23d Ranger Battalion, who was awarded the Medal of Honor for valor on 4 – 8 April 1970. Additionally, Colonel Lewis L. Millett, a Medal of Honor recipient during the Korean War, was a member of the first Vietnamese Ranger MTT. Staff Sergeant David Dolby who was previously awarded the Medal of Honor while serving with the First Cavalry Division in 1965, was an advisor to the 44th Ranger Battalion in 1970. LTC Andre Lucas, who served as Senior Advisor, 33d Ranger Battalion in 1963, later received the Medal of Honor posthumously while commanding an infantry battalion in the 101st Airborne Division in 1970. First Sergeant David H. McNerney, who was an advisor with the 20th Special Battalion in 1962, was later awarded the Medal of Honor while serving with Company A, 1st Battalion, 8th Infantry, 4th Infantry Division for actions on 22 March 1967. More than two dozen Ranger Advisors received the Army Distinguished Service Cross or the Navy Cross, the second highest valor award. Finally, nearly 50 American Advisors were killed while fighting alongside their Vietnamese Ranger counterparts. Theirs was the ultimate sacrifice in the performance of their duty.

Memorial

On 11 November 1995, more than 20 years after the fall of Saigon, American Ranger Advisors and their Vietnamese Ranger counterparts gathered at Arlington National Cemetery to unveil a living memorial and bronze plaque to honor their comrades. The plaque reads, “Dedicated to the honor of the Vietnamese Rangers and their American Ranger Advisors whose dedication, valor and fidelity in the defense of freedom must never be forgotten.”

C/75th & E/20 LRP

Company C (RANGER), 75th Infantry

On 25 September 1967, Company E (Long Range Patrol), 20th Infantry (Airborne) was activated and assigned to I Field Force Vietnam, commanded by Lieutenant General William B. Rosson. The unit was originally formed in Phan Rang by procuring combat veterans from the 1st Brigade (LRRP), 101st Airborne Division, along with personnel who were scheduled to join the Military Police Brigade. Additional assets were also drawn from the replacement detachments.

Company E was originally commanded by Major Danridge M. Malone. The unit was to provide long range reconnaissance, surveillance, target acquisition, and special type missions on a corp level basis. In addition, the company had the capacity to operate as a platoon size force and conduct regular recon-in-force missions. They were known as Typhoon Patrollers, taken from the codeword Typhoon favored by I Field Force headquarters.

On 15 October 1967, Company E was placed under operational control of the 4th Infantry Division, and was relocated to the Division’s base camp at Camp Enari in the western Pleiku Province. The company trained through December and phased its four platoons through ten day preparatory courses, followed by sequential attendance at the MACV Recondo School in Nha Trang, which was run by Special Forces cadre, at two week intervals. Each Platoon concluded their training with a one week field training exercise outside the Special Forces camp at Plei Do Mi in the Central Highlands. The first platoon completed its program on 1 December and the entire company was declared combat operational on 23 December 1967.

Company E was organized for 230 men, broken down into four platoons of seven six-man teams each. A headquarters section handled all the administration and logistics and a communications platoon was responsible for the vital radio contact with the teams. Although the company was designed to field two active platoons while the other two platoons trained and prepared for further missions on a rotating basis, it wasn’t long before every platoon was tasked with their own mission at the same time.

Each platoon consisted of a platoon leader (2nd Lt.), a platoon sergeant (SFC), the seven teams and communications support as required. Active platoons were deployed to mission support sites, such as Special Forces camps and forward fire bases. Each team was structured for a team leader (SSG,SGT), an assistant team leader (SGT,SPC), a radio operator (SPC,PFC), and three scouts (SPC,PFC) and were designated by platoon and team number within the platoon. Second platoon, team 1 would be team 21. As time went by and personnel were rotated out, for a variety of reasons, it was not uncommon for a team to consist of five men or less and to be led by a specialist (E-4). Also due to limited available resources it was not uncommon for a platoon to deploy with only three six-man recon teams. This did not keep the teams from completing any assigned mission, and after training together as a team the men were capable of handling each others duties and positions regardless of their rank. On some occasions two or more teams would be combined (two-teamer) for specific missions such as a reaction force, prisoner snatch, or downed aircraft search/recovery (SAR).

In January 1969 the Army reorganized the 75th Infantry under the combat arms regimental system as the parent regiment for the various infantry patrol companies. On 1 February, Company C (Ranger), 75th Infantry, was officially activated by incorporating the Company E “Typhoon Patrollers” into the new outfit. The Rangers were known as “Charlie Rangers” in conformity with C in the ICAO phonetic alphabet. Company C continued to operate under control of I Field Force and was based at Ahn Khe.

From 4 to 22 February 1969, three platoons rendered reconnaissance support for the Republic of Korea 9th Division in the Ha Roi region and two platoons supported the Phu Bon province advisory campaign along the northern provincial boundary from 26 February to 8 March. Company C then concentrated its teams in support of the 4th Infantry Division by reconnoitering major infiltration routes in the southwestern HINES area of operations until 28 March. During the first part of the year, teams also pulled recon-security duty along the ambush prone section of Highway 19 between Ahn Khe and the Mang Yang pass.

During March 1969, Lt. Gen. Charles A. Corcoran assumed command of I Field Force and an enhancement of Ranger capability was begun. Company C constructed a basic and refresher training facility at Ahn Khe and conducted a three-week course for all non-recondo-graduate individuals during April. The company then used the course for new volunteers before going to the MACV Recondo school. In late April, Company C shifted support to the 173rd Airborne Brigade’s Operation WASHINGTON GREEN in northern Binh Dinh Province. Company C assisted Company N by conducting surveillance of enemy infiltration routes that passed through the western mountains of the province toward the heavily populated coastline.

Most Company C assets remained in Binh Dinh Province in a screening role, but at the end of April one platoon was dispatched for one week in the Ia Drang Valley near the Cambodian border. This was followed by two platoons being kept with the ROK Capital Division on diversionary and surveillance operations through mid July.

On 21 July the company received an entirely new assignment. Company C was attached to Task Force South in the southernmost I Field Force territory operating against Viet Cong strongholds along the boundary of II and III Corp Tactical Zones. The company, now under the command of Maj. Bill V. Holt, served as the combat patrol arm of Task Force South until 25 March 1970.

The Rangers operated in an ideal reconnaissance setting that contained vast wilderness operational areas, largely without population or allied troop density. Flexible patrol arrangements were combined with imaginative methods of team insertion, radio deception, and nocturnal employment. Numerous ambush situations led Company C to anticipate an opportunity to use stay-behind infiltration techniques. As one team was being extracted, another team already on the chopper would infiltrate at the same time on a stay behind mission. The tactic was to be very successful. The company operated in eight day operational cycles and used every ninth day for “recurring refresher training”. The teams rehearsed basic patrolling techniques varying from night ambush to boat infiltration. Ranger proficiency flourished under these conditions, and MACV expressed singular satisfaction with Company C’s results.

The Viet Cong had taken advantage of the “no man’s land” of Binh Thuan and Binh Tuy provinces straddling the allied II and III corp tactical zones to reinforce their Military Region Six headquarters. Company C performed a monthly average of twenty-seven patrols despite inclement weather in this region and amassed a wealth of military intelligence.

On 1 February 1970 the company was split when two platoons moved into Tuyen Duc Province and then rejoined on 6 March. Numerous team sightings in the Binh Thuan area led to operation HANCOCK MACE. Company C was moved to Pleiku city on 29 March 1970, and placed under operational control of the aerial 7th Squadron of the 7th Cavalry where they conducted thirty-two patrols in the far western border areas of the Central Highlands.

On 19 April the company was attached to the separate 3rd Battalion, 506th Infantry and relocated to Ahn Khe, where it was targeted against the 95th NVA Regiment in the Mang Yang Pass area of Binh Dinh Province. The rapid deployments into Pleiku and Ahn Khe provided insufficient time for teams to gain sufficient information about new terrain and enemy situations prior to insertion and they sometimes lacked current charts and aerial photographs. Company C effectiveness was hindered by poor logistical response, supply and equipment shortages, and transient relations with multiple commands. These difficulties were worsened by commanders who were unfamiliar with Ranger employment. Thus, the Rangers performed routine pathfinder work and guarded unit flanks as well as performing recon missions.

On 4 May 1970 the company was opconned to the 4th Infantry Division. The following day Operation BINH TAY I, the invasion of Cambodia’s Ratanaktri Province, was initiated. Although Ranger fighting episodes in the BINH TAY I operation were often fierce and sometimes adverse, the operation left Company C with thirty patrol observations of enemy personnel, five NVA killed, and fifteen weapons captured. On 24 May 1970 Company C was pulled out of Cambodia and released from 4th Infantry Division control.

Four days later they were rushed to Dalat to recon an NVA thrust toward the city. Their recon produced only seven sightings but an enemy cache was discovered containing 2,350 pounds of hospital supplies, and 50 pounds of equipment. They remained in Dalat less than a month before being sent back to rejoin Task Force South at Phan Thiet. May, June and July of 1970 were described by the new commander of Company C, Maj. Donald L. Hudson, as involving a dizzying pattern of operations. The company operated in Binh Thuan, Lam Dong, Tuyen Duc, Pleiku, and Binh Dinh provinces during this time. Twenty-seven days were devoted to company movements with sixty-five days of tactical operations, each move necessitating adjustment with novel terrain, unfamiliar aviation resources, and fresh superior commands.

On 26 July 1970 Company C was transported by cargo aircraft to Landing Zone English outside Bong Son and was returned to the jurisdiction of the 173rd Airborne. The company supported operation WASHINGTON GREEN in coastal Binh Dinh province with small unit ambushes, limited raids, and pathfinder assistance for heliborne operations.

During August, “Charlie Rangers” attempted to locate and destroy the troublesome Viet Cong, Khan Hoa provincial battalion, but were deterred by Korean Army jurisdictional claims. The mission became secondary when the 173rd discovered a large communist headquarters complex at secret base 226 in the Central Highlands and on 17 August the 2nd Brigade of the 4th Infantry Division moved into the region and Company C was attached for reconnaissance.

In mid November 1970 Company C was attached to the 17th Aviation Group, and it remained under either aviation or 173rd Airborne Brigade control for most of the remaining duration of its Vietnam service.

Following the inactivation of I Field Force at the end of April 1971, Company C was reassigned to the Second Regional Assistance Command, and on 15 August was reduced to a brigade strength Ranger company of three officers and sixty-nine enlisted men. The I Field Force rangers were notified of pending disbandment as part of Increment IX (Keystone Oriole-Charlie) of the Army redeployment from Vietnam. Company C (Airborne Ranger), 75th Infantry commenced final stand-down on 15 October 1971 and was reduced to zero strength by 24 October. On 25 October 1971 Company C was officially inactivated.

Company D (RANGER), 75th Infantry

Company D (Ranger) 75th Infantry was formed on 20, November 1969, with a cadre of regular army personnel from Company D (Ranger) 151st Infantry, many of whom were veterans of other tours of duty in country. Major Richard W. Drisko was appointed as the Commander.

The Rangers referred to themselves as the “Delta Rangers” in conformity with the letter “D” of the ICAO phonetic alphabet adopted by the U.S. military in 1956. On 1 December, the new Ranger company was placed under the operational control of the aerial 3d Squadron, 17th Cavalry.

Intensive Ranger training was conducted to prepare the new unit for combat reconnaissance operations. Each of the field platoons completed a seven-day preparatory program that included instruction on communications, map reading, tracking, prisoner snatches, demolitions, ambush techniques, sensor emplacement, and familiarization with repelling, rope ladders, and McGuire rigs. Four Rangers were sent to the sniper school and graduated on 28 January 1970, giving the company sharpshooter capability for special countermeasure patrols. Ranger Company D was given the mission of providing corps-level Ranger support to II Field Force Vietnam by collecting intelligence, interdicting supply routes, locating and destroying encampments, and uncovering cache sites. The Ranger surveillance zone was expanded to encompass the former Indiana Ranger area of operations, as well as the Northeastern portion of the Catcher’s Mitt western War Zone D in Bien Hoa and Long Khanh provinces. The Delta Rangers concentrated on ambush patrols but also performed point, area, and route reconnaissance with elements as small as three men.

On 2 December 1964, a Delta Ranger ambush killed a transportation executive officer of the communist Subregion 5 who was carrying the enemy payroll, capturing 30,500 Vietnamese plasters. In early January 1970, a nine-man combined ambush group, composed of Ranger teams 14 and 15, killed eleven North Vietnamese soldiers from the 274th Regiment of the 5th VC Division and fixed its location for higher headquarters analysis.

The North Vietnamese and Viet Cong instituted increased precautions against Ranger tactics by assigning more trail-watchers to landing fields, mining or booby-trapping routes that they no longer intended to use, and forming counter-raider teams. These enemy teams consisted of four soldiers who were highly skilled in tracking patrols and heavily armed with light machine guns and rocket-propelled grenades.

On 8 February 1970, Ranger Company D was released from 3d Squadron, 17th Calvary, and placed under the operational control of the 199th Infantry Brigade. The Delta Rangers continued operating in southwestern War Zone D and the eastern Catcher’s Mitt area. On 18 March, Ranger Company D returned to direct II Field Force Vietnam control; it was employed to sweep the Nhon Trach district and train recon members of the South Vietnamese 18th Division.

At the end of March 1970, the Delta Rangers ceased operations and commenced stand-down procedures. Company D (Ranger), 75th Infantry, was reduced to zero strength by the afternoon of 4 April and was officially inactivated on 10 April 1970. During the unit’s Vietnam service, the Delta Rangers performed 458 patrols that reported seventy separate sightings of enemy activity and clashed with NVA/VC forces on sixty-five occasions. The Rangers killed eighty-eight enemy soldiers by direct fire and captured three, while suffering two killed and twenty-four wounded Rangers in exchange. Of supreme importance, the Ranger company unmasked changing enemy unit displacements and supply channels aimed against the main allied bases outside Saigon.

II Field Force Vietnam was well served by a succession of highly proficient combat reconnaissance units. The requirements to safeguard the allied capital area placed a tremendous burden on corps-responsive teams to provide accurate and timely information. Fortunately, the patrolling expertise and professional Ranger spirit of the Hurricane Patrollers, Indiana Rangers, and Delta Rangers enabled them to render excellent recon support in South Vietnam’s most crucial region. In many cases, however, their reconnaissance specialty was sacrificed by higher commanders who utilized the units as a “special field force reserve” of light infantry strike forces.

D/151 LRP/Ranger

Company D (RANGER), 151st Infantry

On 20 November 1969, Co D (Ranger), 151st Infantry (Airborne) ‘Stood Down’. Mission accomplished, job well done!

The operations were turned over to Company D (Ranger), 75th Infantry, just as smoothly as they had been turned over from Company F, 51st Infantry (LRP) on 26 December 1968. What is so significant about this change of designation is that Company D (Ranger), 151st Infantry (Airborne) was a National Guard unit from Indiana. Before we discuss the ‘Stand Down’ perhaps a little history of how this unit arrived in Vietnam in the first place would be more appropriate. In November of 1965 the Indiana National Guard organized its’ first and only Airborne Infantry battalion in response to the high mobilization priority Selected Reserve Force. With the build up of the Vietnam war, the entire 38th Infantry Division fully expected to be called to active duty and the inclusion of an Airborne Battalion would be highly valued.

In December 1967 the Department of Defense changed its direction and restructured the National Guard throughout the United States, thus changing the status of the 38th Infantry Division. The Indiana Adjutant General was able to retain most of the Airborne qualified personnel and formed two long range patrol companies. Thus, was born Companies D & E (Long Range Patrol), 151st Infantry, later to be combined into a single company, designated Company D. Ironically most training on weekend drills was divided between long range patrolling techniques and riot control training.

War in Vietnam continued to escalate and so did the resistance at home. Several states were utilizing the Guard to control demonstrations, especially on college campuses. A new twist came when it was announced that summer camp training for 1968 would be held in March at the Army’s Jungle Warfare Training Center in the Panama Canal Zone. You can imagine what rumors started flying when the cadre at the Jungle School started telling the members that they were headed for Vietnam. No one could believe it when just three weeks after returning from Panama the unit was called to active duty.

On Monday May 13, 1968 the unit departed from Indianapolis, Indiana for Ft. Benning, Georgia. Of all the 20,000 reservists activated, D Company was the only infantry unit of the National Guard in the United States. A total of 195 enlisted men, 1 warrant officer, and 8 officers convoyed in World War II vintage trucks to Georgia on the same day that the peace talks started in Paris, France.

All members were already jump qualified and 98% were jungle qualified. Co D would undergo 6 months of additional training with the 197th Infantry on Kelly Hill. Several members were sent TDY for special schools, including Radio school and Ranger school. The entire unit spent one week each at the three Ranger school courses in Georgia and Florida. Several jumps were made at Benning in the 6 months while in training.

Rumors were rampant among the men up until departure day, that the unit would never go to Vietnam. On December 20, 1968, 6 men departed as an advance team to set up the base camp which was to be located next to the 199th Light Infantry Brigade, in an old missile base. On December 28, 1968 the entire unit left for Bien Hoa. By this time about 20% enlisted and drafted men joined the unit taking the place of those National Guard personnel that had been transferred or ETS’d.

Only after arriving in Vietnam did the unit find out that they would be replacing another Long Range Patrol company that was being dismantled. We were told that due to severe losses the unit could no longer function. Obviously, some higher ups had to justify us being there. Later, when members of Company F, 51st began transferring in to D Co, we learned the real truth. Co F was doing a great job and all were extremely upset that we had taken their place. Things calmed down a great deal when Co F’s commander Major Heckman took over as commanding officer of Company D. Years later we would learn that someone in the Indiana National Guard made a deal with the Department of the Army in Washington that the unit would stay together and not be dismantled. Other reservist that were activated were sent to Vietnam on an individual replacement basis (sans an artillery unit from Bardstown, Kentucky).

The 199th Light Infantry Brigade conducted a one week orientation course with the unit. Physical training became intense and difficult. The unit had just left Indiana winter and a 30 day leave of absence, and Vietnam’s summer heat was a difficult adjustment. The unit was attached to the II Field Force to become their eyes and ears in the free fire zones north of the Bien Hoa Air Force base and Long Binh.

Work was around the clock getting the base camp set up and all the supplies and equipment in place. By mid January 1969 members were going on patrol with members of F Co for long range patrol orientation. By February, the unit had passed it’s test and was deemed operational. At the same time the unit’s status and name was changed from Long Range Patrol to Ranger. Patrolling was on a regular schedule by then with all 12 to 18 teams in the field at all times. 30 members attended the MACV Recondo school run by the 5th Special Forces at Nha Trang, all graduating with the Arrowhead patch and diploma.

In March the Company received Chieu Hoi scouts which were assigned to the teams. The new team members were received with caution, but after a few patrols and contacts, the Chieu Hois were very much accepted and welcomed with few exceptions.

After a briefing by II Field Force Intel Officer, in which the company was told that the only true information was bodies, equipment, and documents. They didn’t seem to trust our reporting from a reconnaissance report. The missions now became more as hunter-killer teams than the true reconnaissance teams.

The members were all highly motivated and well educated. All were older than the typical Vietnam personnel. The average age of the members was around 24. Several were in college, or had well established careers.

Many ambush patrols into the “D Zone” along trails, and the Song Dong Nai and the Song Bong rivers. Several patrols reported a massing of the enemy troops during the Tet of 1969. Most patrols were 5 or 6 man teams, but several heavy 12 man patrols were conducted if previous information suggested that a contact was likely. Many contacts were made by the teams against 3 to 4 NVA/VC patrols, but there were some teams that initiated on much larger enemy forces.

One heavy mission in May 1969 counted 380 NVA as they advanced south. On this particular night, the team did not pull back to a RON, but stayed up on the trail within 5 feet of it. Indirect fire claimed many enemy lives, as it was directed by the Ranger team on the ground.

As some of the initial National Guardsman rotated out due to ETS, hardships, wounds, and early out for college, regular army personnel were recruited or assigned to take their place. These new members were well trained by the time the company “Stood Down”. In early November 1969, the remaining National Guard members were moved from the base camp at Long Binh to Bien Hoa in preparation for the units’ return to Indiana.

Six members of the unit made the supreme sacrifice on Ranger missions. They, and lots of other members were decorated for Valor and Duty. In all, 19 Silver Stars, 175 Bronze Stars, 86 Army Commendation Medals, 120 Air Medals, 110 Purple hearts, 19 Indiana Distinguished Service Crosses, and 204 Indiana Commendation Medals were awarded. On November 20, 1969 Company D (Ranger), 151st Infantry (Airborne) became Company D, 75th Ranger. The 75th was made up of the 151st Rangers as well as new members, and continued to carry on the same missions operating from the same base camp at Long Binh until they “Stood Down” later in 1969.

E/75 & E/50 LRP & 9th Div. LRRP

Company E (RANGER), 75th Infantry

This history deals with the activities, personnel and accomplishments of Company E (Ranger), 75th Infantry during the period 1 February 1969 through 12 October 1970 and makes reference to the units who preceded the designation of Company E (Ranger), 75th Infantry.

Throughout history the need for a small, highly trained, far ranging unit to perform reconnaissance, surveillance, target acquisition, and special type combat missions has been readily apparent.

In Vietnam this need was met by instituting a Long Range Patrol program to provide each major combat unit with this special capability.

Rather than create an entirely new unit designation for such an elite force, the Department of the Army looked to its rich and varied heritage and on 1 February 1969 designated the 75th Infantry Regiment, the present successor to the famous 5307th Composite Unit (MERRILL’S MARAUDERS) as the parent organization for all Department of the Army designated Long Range Patrol (LRP) units and the parenthetical designation (RANGER) in lieu of (LRP) for these units. As a result, the 50th Infantry Detachment (LRP), formally the 9th Infantry Division LRRP (Provisional) assigned to the 9th Infantry Division, became Company E (Ranger), 75th Infantry.

In the fall of 1966, the 9th Infantry Division formed a division Long Range Reconnaissance Patrol (LRRP) Platoon after division commander, Maj. Gen. George S. Eckhardt flew to Vietnam on an orientation tour of the combat theater. Major General Eckhardt noted that each division contained a long-range patrol unit. He arrived back at Fort Riley, Kansas, where the Division was completing preparations for its scheduled December deployment to Vietnam, and ordered the immediate organization of a reconnaissance platoon for his own division. Capt. James Tedrick, Lt. Winslow Stetson, and Lt. Edwin Garrison were chosen as the officers for the LRRP Platoon. They interviewed and screened the records of 130 volunteer soldiers and selected the best 40. The provisional unit was known as the “War Eagle Platoon”. In November of 1966, the LRRP Platoon completed the Jungle Warfare School in Panama. Captain Tedrick conducted an extra week of tropical training following the regular two-week course. Platoon members were shipped to Vietnam in January 1967.

At the Special Forces MACV Recondo School at Nha Trang, the entire 9th Infantry Division LRRPS became recondo-qualified, Meanwhile, the unit adjusted to its combat operating area. The division operated primarily in the lowlands south of Saigon, the Rung Sat Special Zone, and the Mekong Delta. Torrential rains and year-round water exposed patrollers to high rates of disabling skin disease. Reconnaissance troops often suffered extensive inflammatory lesions and rampant skin infections. And by the fourth month of tropical service, nearly three-fourths of all infantryman had recognizable infections. The Bear Cat – Long Thanh area east of Saigon was where the division was initially concentrated. The new base, Dong Tam, was constructed by dredging the My Tho river to produce enough fill to build a major installation in the Mekong Delta. It was located five miles west of My Tho in Dinh Tuong Province.

On 8 July 1967, the 9th Long Range Patrol Detachment (LRPD) was formalized. Borrowing General Marshall’s World War II phrase, the Division LRPD was “well brought up.” During June and July, the LRPD completed forty-three patrols and clashed eighteen times with enemy forces. Through August and September, the LRPD continued to fill. By October it had reached full authorized strength of 119 personnel and was rated fully operational. Each platoon contained a command section and eight, six-man teams. Some teams of the division LRPD rendered reconnaissance for 2nd Brigade in Operation CORONADO and entered the Viet Cong Cam Son secret base area while other teams supported the 1st Brigade in Operation AKRON and uncovered a massive underground system of enemy tunnels and bunkers. The LRPD also conducted important military intelligence tasks for the Mobile Riverine Force within the Mekong Delta.

Major General George C. O’ Connor activated Company E (Long Range Patrol), 50th Infantry, to give the 9th Infantry Division specialized ground reconnaissance support on 20 December 1967. The long-range patrol company absorbed the LRPD and was designated as “Reliable Reconnaissance” after the division nickname of “Old Reliable’s.” During January 1968, the Navy SEAL teams began joint operations with Reliable Reconnaissance. LRP’s did this to gain training and experience in the Delta environment The missions designated as SEAL-ECHO were the highly selective patrols. They were inserted by Navy patrol boats, plastic assault boats, helicopters, and Boston whalers. The SEAL-ECHO troops used supporting artillery and airstrikes to destroy larger targets.

Maj. Gen. Julian J. Ewell assumed command of the 9th Infantry Division in February 1968. He authorized the Reliable Reconnaissance company to acquire a similar capacity to the 3rd Brigade Combined reconnaissance and Intelligence Platoon as a result of the Tet-68 battles. Company E received permission to employ available Provincial Reconnaissance Unit (PRU) personnel from the Central Intelligence Agency’s Project Phoenix program. The PRU troops were hardened anti-communist troops dedicated to destroying the Viet Cong infrastructure. The PRU troops generally possessed very high esprit and great knowledge of Viet Cong operating methods. From November 1968 through January 1969, the last three months of Company E’s existence, the Reliable Reconnaissance teams conducted 217 patrols, and engaged the enemy in 102 separate actions. The company was credited with capturing eleven prisoners and killing eighty-four Viet Cong by direct fire. On 1 February 1969, the department of the Army reorganized the 75th Infantry as the parent regiment for long-range patrol companies under the combat arms regimental system. Maj. Gen. Ewell activated Company E (Ranger), 75th Infantry, from Company E, 50th Infantry. The Rangers were known as “Echo Rangers” or “Riverine Rangers,” because they mostly dealt with river and canal reconnaissance – even though the company was only partially assigned to the Mobile Riverine Force. Ranger Company E took advantage of dry season conditions to harass suspected Viet Cong supply lines from activation until the end of April. The Riverine Rangers conducted 244 patrols and reported 134 observations of enemy activity. They clashed with the Viet Cong during 111 patrols and were credited with capturing five prisoners and killing 169 Viet Cong. When the 9th Infantry Division began phasing out of Vietnam in July 1969, the rangers renamed themselves “Kudzu Rangers” after the operational code word for the close-in defense of Dong Tam. The ranger company phased its teams out of the Kudzu business by 3 August.

On 23 August 1969, the Army formally inactivated Company E (Ranger), 75th Infantry. The provisional ‘Go-Devil” Ranger company, also known as the separate 3rd Brigade of the 9th Infantry Division, formally established as an independent unit on 26 July 1969, was unaffected by this paper ruse. On 24 September, the U.S. Army Pacific reactivated Company E by General Order 705 and the U.S. Army Vietnam headquarters published orders re-assigning Company E to the 3rd Brigade, 9th Infantry was again activated on 1 October 1969 and the original Company E was discontinued and became the new Company E. The only difference was what they called themselves, They dropped “Riverine Rangers” and continued on with their newly acquired name, “Go-Devil” Rangers.”

No other combat recon units waged reconnaissance and intelligence gathering operations under circumstances more difficult than those with the 9th Infantry Division in Vietnam. Despite this, the Reliable Reconnaissance Patrollers, Riverine Rangers, and Go-Devil Rangers manifested sound tactical doctrine and imaginative techniques in adjusting to the alien Mekong Delta environment and applied undeviating pressure against the Viet Cong havens and their supply lanes throughout the division term of service in Vietnam.

Company E (Ranger), 75th Infantry is entitled to the following:

Campaign Streamers: Vietnam

Counteroffensive Phase VI

TET 69 Counteroffensive

Summer-Fall 1969

Winter-Spring 1970

Sanctuary Counteroffensive

Counteroffensive Phase VII

Consolidation I

Consolidation II

CEASE FIRE

Decorations: Vietnam:

RVN Gallantry Cross w/Palm

RVN Civil Actions Honor Medal

Traditional Designation: Echo Rangers

Motto: Sua Sponte (“Of their own accord”)

Distinctive Insignia: The shield of the coat of arms

Symbolism of the coat of arms: The colors: Blue, white, red, and green represent four of the original six combat teams of the 5307th Composite Unit (Provisional) which were identified by a color code word. The units close cooperation with the Chinese forces in the China-Burma-India Theatre is represented by the Sun symbol from the Chinese Nationalist Flag. The white star represents the Star of Burma. The lightning bolt is symbolic of the strike characteristics of the behind-the-line activities.

RANGER Designation:

Rationale – – The rationale for selecting the 75th Infantry as the parent unit for all Department of the Army authorized Ranger units is/was as follows:

(1) Similarity of missions between those missions performed by Merrill’s Marauders and the 75th Infantry, Ranger Companies in the republic of Vietnam and those of the 75th Ranger Regiment – – Operations deep in enemy territory.

(2) It returns to the rolls of the active Army Regiment having a distinguished combat record and a unique place in the annals of the United States Army.

(3) It provides the 75th Ranger Regiment and the United States Army with a common regimental designation identifying an uncommon skill.

F/75 & F/50 LRP & 25th Div. LRRP

Company F (RANGER), 75th Infantry

The 25th Infantry Division (LRRP) (Provisional) assigned to the 25th Infantry Division, became Company F (Ranger), 75th Infantry and existed in this unit designation from 1 February 1969 to 15 March 1971.

The 25th Infantry Division arrived in Vietnam from Hawaii in two major groups. The 3rd Brigade deployed as a task force arriving in Pleiku, Corps II region of Vietnam on28 December 1965. The 3rd Brigade would later have its own LRRP contingent and also be traded to the 4th Infantry Division for a brigade in August 1967. The remaining brigades and headquarters arrived at Cu Chi in Corps III area from 20 January 1966 through 4 April 1966.

It quickly became apparent to Major General Fred C. Weyand that a reconnaissance/specialty unit was needed to supplement 3rd Squadron, 4th Cavalry who were mounted troops and had the mission of providing road security and were ill equipped or trained to perform dismounted reconnaissance missions. General Weyand authorized the formation of the Long Range Reconnaissance Patrol detachment and forty-one officers and enlisted personnel were selected for duty with the unit. The unit was known as “Mackenzie’s Lerps” because it was assigned to the 4th Cavalry known as Mackenzie’s Raiders after Colonel Slidell Mackenzie who had commanded the unit from 1870 to 1882 with proficiency.

Training for the new LRRPs was accomplished at the Special Forces MACV Recondo School at Nha Trang. The unit started patrolling at increasing distances from the Division and fire support bases. Missions included waterborne operations and were primarily oriented to finding the enemy so U.S. firepower could be staged and brought to bear on the enemy. Other types of missions including prisoner snatch, ambush, etc. were ordered for the normal five man teams.

On the job experience added Standard Operating Procedures (SOP) for later volunteers to the unit. The only way into the unit was to volunteer and the members could be reassigned by unvolunteering themselves for less hazardous duty in a rifle unit. Allocations to Nha Trang and length of training time encouraged the formation of a 25th Division Recondo School which quickly brought volunteers to a workable patrol knowledge level.

LRRP was given a TO&E personnel strength of 60 plus, but, its real strength was closer to half that while its address was D Troop (LRRP), 3rd Squadron, 4th Cavalry. A remarkable amount of useful patrol knowledge was passed on in these classes always bearing the indelible stamp of the original Nha Trang training by the Special Forces. The word “Reconnaissance” is somewhat misleading because missions were often combat in nature stemming from the desire of patrollers and commanders to do more than just look. Missions often were ended with an ambush or were interrupted by targets of opportunity. This was a prevailing attitude in the field and base commanders. While the 25th Division was in Cu Chi, its 3rd Brigade was still in Pleiku with its LRRPs referred to as “Bronco LRRP’s”. The Brigade LRRP teams existed from mid-1966 to August 1967, participating in 7 major operations from the border west to the South China Sea east including Duc Pho and Qui Nhon.

The Department of the Army officially authorized the formation of Company F, 50th Infantry Detachment (LRP) on 20 December, 1967. LRP stood for Long Range Patrol which more closely represented the missions. This unit was formed with the personnel and equipment from the LRRP detachment. The combat nature of the unit was borne out when General Weyand said in March 1967 that LRRP was the “fightingest unit under his command”.

The 50th Infantry continued to operate in III Corp region of Vietnam which included War Zones C and D which contained the floating enemy command for all of Vietnam (COSVN). The 50th Infantry was now known as the Cobra Lightning Patrollers and continued to operate in areas such as Tay Ninh, Fish Hook, Parrots Beak, and Angels Wing along the Cambodian border. Actions initiated on 28 January 1968 by the LRPs resulted in the KIA of 64 Viet-Cong reconnaissance troops.

Credit needs to be given to the personnel of the LRRP platoon and the 50th Infantry Detachment (LRP) for establishing the doctrine that would become SOP for Company F (Ranger), 75th Infantry. The 75th Infantry absorbed the personnel and equipment of the 50th Infantry detachment (LRP) on 1 February 1969. They were now known as “Fox Rangers” from the phonetic “F” and “Tropical Rangers” from the Division’s name “Tropic Lightning”. Rangers included one sniper qualified trooper on each team. Ranger training started in the U.S. and was more refined than ever based on intelligence and experience gathered by Vietnam Ranger parent units (LRRP & LRP). This produced extremely qualified personnel well able and motivated to do the dangerous missions of the Rangers.