Last Charge at Mogadishu - 10th Mountain Division and Task Force Ranger

This article, my first professional writing effort, was written in 2001 for Osprey Publishing. It was not published because the particular journal ceased publication before my submission. I left it in its original unedited version making only a couple of comments in brackets. Pictures were kindly provided by 3/75 Mogadishu veteran Ranger Anton Berendsen and Mogadishu Veteran Mark Jackson of the 10th MD.

THE LAST CHARGE AT MOGADISHU

To someone who has never experienced danger, the idea is attractive rather than alarming. You charge the enemy, ignoring bullets and casualties, in a surge of excitement. Blindly you hurl yourself toward icy death, not knowing whether you or anyone else will escape him. Before you lies that golden prize, victory, the fruit that quenches the thirst of ambition. Can that be so difficult?

Carl von Clausewitz

With the war drums banging and the trumpets calling the civilised nations to arms against terrorism it would be prudent to review a small and seemingly insignificant action involving United States and United Nations troops that took place in Mogadishu, Somalia from October 3-4, 1993; the Battle of the Black Sea. As the democratic states are vying for alliances to rid the world of “evil-doers”, one must remember that at the end of the day, no matter the cause, it is the common soldiers who must stand their ground and do or die. In the years to come, these often unheralded and much maligned foot soldiers will have to be able to work effectively with their foreign counterparts as joint task forces will undoubtedly bear the brunt of this new war on terrorism as they did in the dusty streets of war-torn Mogadishu.

The purpose of this article is three-fold. First of all, it is to familiarise the reader with the complexities and difficulties of waging a battle with multi-national forces against an indigenous hostile people. Secondly, it is intended to explain the poor view special operations forces have of regular troops and lastly, albeit to a very small degree, show the far-reaching arm of world-renown guerrilla, Osama bin Laden. However, it is by no means a complete analysis of this rather complex battle.

SOMALIA

It is like a porcupine, bristling with quite exceptional difficulties.

J.F.C. Fuller, 1935

Somalia has been a war-ravaged country for centuries, and fighting is a way of life there whether striking fear into the hearts of British squares, Italian colonial troops or waging war against each other, Somalia was, is and will continue to be an armed and hostile land. Somalis battled their neighbours, changed strategic alliances with super powers and struggled to survive a civil war. Inevitably, this left the country exhausted, impoverished and fragmented in the latter part of the 20th century.

In the early 1990’s images of poverty, starvation and violence flooded across billions of television sets worldwide as humanitarian relief missions struggled to deal with a vast army of doped up, gun-toting youths, looking for the enormous wealth associated with these humanitarian organisations. The strongest or most vicious thrived at the expense of the weaker. Relief workers were threatened or killed and aid shipments were taken by force. Subsequently, the United Nations, led by the United States, committed troops to oversee the safety of workers and proper distribution of aid in December of 1992.

A change in the original UN mission, from humanitarian relief to nation building, culminated with an arrest warrant to capture those held responsible for the deaths of numerous peacekeeping troops. The main enemy declared was the Habr Gadir clan chief, Mohammed Farah Aideed, the head of the Somali National Alliance and a very powerful Somali indeed. Following the death of more American soldiers, the US dispatched a special operations force, Task Force Ranger, on August 26th, 1993. Its sole purpose was to hunt down Mohammed Aideed and his top lieutenants.

Yet, in the late afternoon of October 3rd, 1993, members of this supreme force found themselves isolated deep in Aideed’s stronghold, with heavy casualties and two downed aircraft, fighting for their lives, surrounded by thousands of well armed and, for ever so brief a moment, united Somalis bent on dealing death. Thousands of women, children and elderly added to the crucible of war as spectators or willing participants. Burning tires and roadblocks spread throughout the city.

In the end, and after a tremendous fight, a much-maligned polyglot of mechanised infantry comprised of Malaysians, Pakistanis and regular American troops relieved the trapped special operations force.

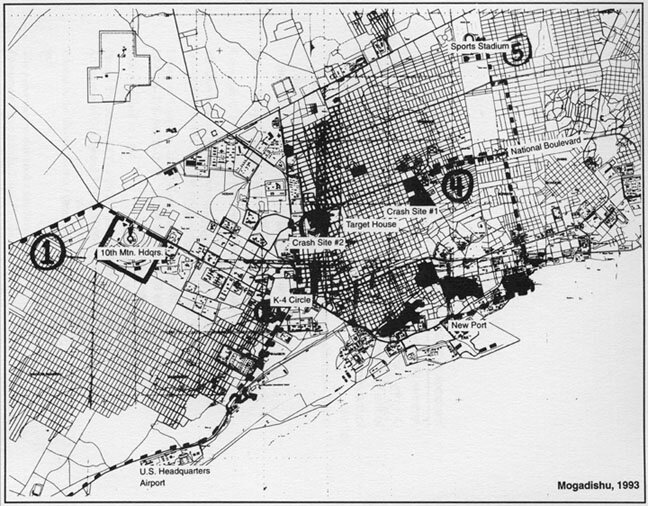

Detailed map of Mogadishu. The intricate and confusing patterns of the city’s grid are visible.

Aerial shot of Mogadishu. In the foreground is the Task Force Ranger compound located at the airport. Credit: Ranger Anton Berendsen

THE MALIGNED REGULAR INFANTRYMAN

In order to appreciate the maligned regular infantryman and his unacknowledged accomplishment during the Battle of the Black Sea, we must first delve into the psyche of the American military elite and its symbol of excellence; the beret. The beret, until the summer of 2001, was authorised to be worn only by very few units, all of which are airborne in nature. The historically celebrated 82nd All American Airborne Division wears maroon, Special Forces are known throughout the world as the Green Berets and Army Rangers wore black berets until 2001 when they switched to tan, similar to the British Special Air Service.

Most of these special soldiers complete arduous selection courses and subsequently view themselves better than the rest of the military, the so-called legs. A leg then is a derogatory term used to describe any “high-drag, low-speed” non-airborne-qualified individual who somehow rather or another failed to measure up to the higher standards of the airborne soldier. Never mind whether they attempted them or not, after all every soldier wants to be in special units. Or so some elitists say. An Army Ranger, for example, would not give the time of day to a “dirty, nasty, stinking leg” and often these disparate attitudes translate into animosity that either creates greater unit cohesion for some or further alienates an already divisive American military.

Elite units also receive a larger budget for better training and superior equipment, contributing even further to the demise of the regular soldier’s reputation. These lesser-trained legs then constitute the bulk of the modern United States Army. And these very same men constituted the 10th Mountain Division that inexorably fought their way through Somali roadblocks and ambushes, died and killed, so that they could rescue their hard-pressed comrades from near certain disaster.

This article then is a paean to those under-appreciated legs that comprised elements of 10th Mountain Division’s Quick Reaction Force and their fight to glory alongside their Muslim brethren, the Pakistanis and Malaysians.

OPPOSING FORCES

Somali Forces

Somalia does not have a regular army. Clans and their fighters rule their respective areas.

In late 1993 the UN no longer patrolled at night and the Somalis completely controlled all areas outside of the UN compounds at night. The Bakara Market, Aideed’s stronghold, contained at least 2,500 experienced fighters within a supportive populace. Standard weaponry included NATO and Soviet Block assault rifles, machineguns, rocket propelled grenades, mines, demolition, armed jeeps and even anti-aircraft systems. Several hundred of these well-armed Somalis had recently returned to Mogadishu fresh from their training at Bin Laden sponsored guerrilla camps. Undoubtedly, instructions included the massing of RPG fire to shoot down helicopters as the Afghani Mujahideen had learnt fighting the Russians over the previous decade. Any student of warfare would have looked to Vietnam for examples of downing American helicopters with small arms fire.

Previous engagements against US and UN troops had shown the Somalis to be able to mass fighters relatively quickly, using high and low technology methods of communication such as hand-held radios, cell phones, tracer rounds, banging pipes or burning tires. The low technology forms of communication rendered US electronic jamming useless during the battle. Somalis were able to construct obstacles and barricades and place mines throughout main arteries of travel. They were not impeded by vehicular movement at all and knew their turf very well. Foreigners found the labyrinthine alleys and streets of Mogadishu confusing.

Somali fighters were experienced, tough, well co-ordinated and on khat, a mild amphetamine.

United States Forces

Task Force Ranger (TFR):

TFR was composed of three main units.

Special Forces Operational Detachment – Delta (SFOD-D), Squadron C.

Delta was founded in 1977 to conduct counter-terrorist special operations. It is predominantly comprised of older soldiers from other special operations units such as Special Forces and Army Rangers.

160th Special Operations Aviation Regiment (Airborne).

This aerial unit was founded to support the needs of Army special operations in 1981. Their ability to strike at night earned them the revered nickname “Night Stalkers.”

75th Ranger Regiment – B Company, 3rd Battalion.

Considered by many to be the best light infantry regiment in the world. Most Rangers are in their late teens or early twenties.

Task Force Ranger was the best-equipped and most well trained force in America’s arsenal. Eight MH-60K Black Hawks, four MH-5 “Little Birds”, four AH-6J “Little Birds” (attack versions) plus support elements completed this 450 strong special operations force package. These units participated in numerous post-Vietnam War operations and since arriving in Mogadishu, TFR had conducted six raids.

10TH Mountain Division

10th Mountain Division is currently headquartered in the unforgiving snow-covered terrain of northern New York State at Fort Drum. The unit was founded as an elite ski troop during World War II and fought in southern Europe. Their motto “climb to glory” would come to the forefront again during various operations throughout the world. But nowhere was it more pressing or urgent to stay true to this motto and to climb over the obstacles than on October 3rd and 4th 1993.

The soldiers of the 2nd Battalion, 14th Infantry Regiment of the 10th Mountain Division, commanded by Lieutenant-Colonel William David, had arrived in country on July 29, 1993 as part of the UN’s commitment to Somalia. They, and several support units, had participated in five major operations before October 3rd , including several intense fire-fights. On September 12, during a combat patrol to attack and seize two compounds thought to be weapons storage facilities, they were ambushed and in a fight for their lives. Only with the help of Pakistani tanks and Cobra gunships from 10th Division’s aviation arm (TF 2-25) were they able to extricate. Over one hundred Somalis were killed in that engagement. On September 25, a TF 2-25 Black Hawk helicopter was shot down by Rocket Propelled Grenades (RPG’s) resulting in one of the fiercest firefights for 2-14.

Allied Forces

Pakistan

The Pakistani contingent had been engaged in several firefights during their stay in Somalia and had suffered the largest UN casualties. Units represented; 15 Frontier Force and 19 Lancers. One tank platoon consisting of T-55’s was provided to the Americans.

Malaysia

Two mechanised companies of German Condors (armoured personnel carriers) totalling 28 vehicles from the Royal Malaysian Ranger Regiment participated in the relief effort.

TRAINING

It is important to note that training in Somalia was excellent for all American units, specifically 2-14 and the Rangers. A document from the 75th Ranger Regiment indicates that Bravo Company conducted their best live fire training in Mogadishu and this from a unit that prides itself on realistic training methods. Rangers and some elements of 2-14 had also trained together in Mogadishu in recent weeks. 10th Mountain Division personnel stated that they were well motivated, well trained and very efficient in urban mounted combat patrols since arriving in Somalia. Certainly by the 3rd of October, 10th Mountain had seen its fair share of action and was competent in its missions. On the job training, ranging from live fire exercises to real world combat patrolling had turned 2-14 into a solid light infantry battalion.

Two Rangers from B/Co, 3rd Battalion, 75th Ranger Regiment pose in front of Little Birds. Credit: Anton Berendsen

OCTOBER 3RD, 1993 – THE UNTHINKABLE

It was another warm afternoon in Mogadishu and the soldiers from 2-14 had been briefed that another raid, the seventh by TFR was in progress and they would as usual provide one company as a Quick Reaction Force (ORF) in the unlikely event that things did not work out. The following blow-by-blow time line shows the myriad face of a well-executed raid that turned into a brutal brawl, all within a few short minutes.

1542 TFR assault teams conduct fast-rope raid near the Olympic Hotel.

1553 Ranger ground reaction force (GRF 1) under Ranger Commander Lieutenant-Colonel McKnight composed of nine Humvees (military jeep) and three five-ton trucks waits in a holding area to retrieve the assault element upon completion of the raid.

1558 The GRF 1 is attacked, losing one five-ton truck and getting one man injured.

1604 The raid is a success netting 24 detainees. One Ranger is injured inserting near the hotel.

1613 GRF 1 arrives at consolidated objective

1620 Black Hawk shot down – Pilot Wolcott – Northern site. GRF 1 loads detainees and injured Ranger on one five-ton truck to return to TFR compound with Humvee escort which it does under fire. GRF 1 enroute to crash site.

1624 A Little Bird lands near crash site and rescues 2 wounded crewmen.

1628 Search and Rescue (SAR) team, fast ropes near crash site as TFR assault elements arrive at site simultaneously.

1628 10th Mountain Division’s QRF, one company (C/Co), directed to TFR compound.

1641 Second Black Hawk shot down – Pilot Durant – Southern site with eventual Delta sniper insertion from another helicopter.

1700 All TFR elements report heavy casualties including GRF 1.

1703 A Ranger force, GRF 2, with 27 soldiers including Ranger cooks departs TFR compound on 7 armoured Humvee and 2 five-ton trucks to secure Durant crash site.

1710-1724 QRF arrives at TFR compound.

1703-1740 GRF 2 fails on all three separate routes. At the last route, north of K-4 circle, GRF 2 runs into shot up GRF 1 under Lt. Col. McKnight. Joins forces, cross-loads wounded and destroys two disabled vehicles. Returns to TFR compound.

160 SOAR Black Hawk and crew.Credit: Anton Berendsen

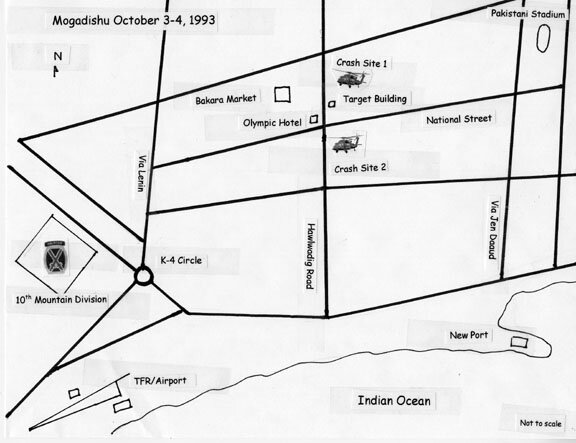

Simple map illustrating the crash sites and main routes of travel.

Immediately following the crash of the first TFR Black Hawk, C/Co, the Quick Reaction Company (QRC), was called in at 1629 Hours. One 2-14 officer recalled seeing the Ranger Liaison Officer attached to 10th Mountain’s Tactical Operations Center (TOC) at the University Compound monitoring the action on headphones “with a concerned look.” Like other QRF missions, very little information was transmitted from Task Force Ranger to the unappreciated 10thMountain’s TOC.

A rare photo taken of TF 2-25’ crashed Black Hawk. The subsequent rescue led to one of the fiercest firefights until the rescue missions on October 3rd. Credit: Mark Jackson

Colonel Lawrence Casper, the overall commander of 2-14 Infantry and their aviation brigade, Task Force 2-25, comprised of Cobras and Black Hawks, informed Lieutenant-Colonel David, that he and his company would fall under the operational control of Major General William Garrison, TFR’s commander. Colonel Casper also ordered the convoy to travel on the longer but safer southern route to the TFR compound at the Mogadishu airport.

The QRC received a briefing, including the locations of the two crash sites, three miles away. Their mission was to secure the second (southern) site. Lt.Col. David devised a simple plan. Travel northeast to the well-known K-4 traffic circle, then north on Via Lenin, east on National Street and finally, south on Hawlwadig Road. At 1740 the convoy departed the TFR compound. The QRC included several individuals from TFR, C Co, 2-14, one AT (anti-tank) Platoon, one squad from the 41st Engineers, one CA (Civil Affairs) team, one PSYOP (Psychological Operations) team plus Humvees and five-ton trucks,

Just north of K-4 and with two miles to go, the convoy ran into a roadblock at Via Lenin and was ambushed. The Somalis unleashed a storm of steel, including 300 plus rounds of RPGs. At about the same time, TFR’s shot up ground convoy from the raid under Colonel McKnight zipped by, still hounded by Somali gunfire. Unable to punch through the lines, with communications problems and air assets taking fire at the UN controlled New Port, the 10th Mountain Division convoy was finally ordered to return at 1821. But the confines of the narrow streets and the continuous firing required 20 minutes for the vehicles to make U-turns and successfully egress. Soldiers had dismounted to cover the withdrawal. During the rearguard engagement First Sergeant Gary Doody and Private First Class Eugene Pamer, of 2-14, received Silver Stars for their actions.

The QRC’s withdrawal was nearly overcome by panic where it not for some individual acts of courage and professionalism. Some vehicles tried to out run slower ones and the convoy scattered. Once away from the fight and a few hundred yards south of K-4, near squatters’ tents made up of mostly garbage, the convoy reformed and accounted for personnel. A single shot or two from the shanty town led to a short-lived massive volley from the convoy tearing the tents and some of its residents into confetti.

Units from 10th Mountain Division patrolling a heavy populated street in Mogadishu. Credit: Mark Jackson

The defeated, scared and angry convoy pulled into the Mogadishu airport a short while later.

By 2030 Hours, Alpha Company, 2-14, plus support arrived at the TFR airport, still not knowing the details of the current situation. Finally briefed, all personnel were aware of the precarious situation of the heavily engaged special forces at the crash sites and the danger of them being overrun.

Major General Thomas Montgomery, the overall commander of all US forces in Somalia and the deputy commander of all UN troops, requested armour and received positive responses from the Italian, Pakistani and Malaysian contingents. The Italians, however, were too far away and distrusted by the US special operations forces (SOF) who claimed that Italians paid off Somali clans and gave away intelligence. The Pakistanis in their antiquated T-55 tanks and the Malaysians’ Condors provided the necessary shields and punching power.

Brigadier General Greg Gile of 10th Mountain was appointed to take charge of the operation. At this point there seemingly were more senior officers than actual combatants. They included Colonel Casper of the QRF, Major General Garrison of TFR, Gile of 10th Mountain, and Major General Montgomery overall Commander.

THE LAST CHARGE

The Americans moved to the new staging areas at New Port and linked up with the Pakistani and Malaysian units. Plans were made and changed again, ammunition and other vital materiel loaded to the best of everyone’s capabilities and limitations. Lieutenant Colonel Bill David would lead his polyglot army into the heart of Mogadishu. English, Pashto, Punjabi, Malay, Chinese and hand and arms signals, coupled with varying abilities and desires had to become a single purpose machine of war and salvation for others. Basic ammunition loads were doubled for the infantry. There would be no turning back.

A 10th M.D. roadblock. This photo gives a good eye level view of the Mogadishu street maze. Credit: Mark Jackson

Until then, several separate attempts had been successfully thwarted by the battle hardened Somalis using nothing more than roadblocks, massed small arms fire, RPGs, mortars and the occasional anti aircraft gun. Elements of Task Force Ranger had failed on three separate routes taken and finally, so had Lt.Col. David’s C/ Company.

Hours had gone by and the situations at the crash sites were desperate. Only the absolute professionalism of the Night Stalkers and their combined acts of unbelievable heroism had prevented complete annihilation of the small task force in Aideed’s stronghold near the Bakara Market. For example, one Little Bird landed in a tight alley. The pilot fired his personnel weapon while controlling the aircraft as his co-pilot rescued several crew members of a downed Black Hawk.

Frustrations were vented. Questions were asked and accusations abounded about the lack of a timely rescue. Certainly they complained, the incompetent 10th Mountain Division was to blame. But what of the three failed attempts?

A typical sandbag reinforced five-ton truck. The truck offered no protection from small arms fire and RPG rounds. Credit: Mark Jackson

Based upon the Pakistanis’ experience and US aerial reconnaissance, the attack was to be made from a north-eastern direction via Jen Daanud to National Street, then south-west on National to Hawlwadig to the Olympic Hotel where A/Co and C/Co would separate into two units. Each company would break through to their crash site and link-up with elements of TFR, then rejoin the main column and finally punch their way through to the Mogadishu airfield. Lt. Col. David’s TOC, the reconstituted Ranger ground reaction force and other support units would form a holding area for casualty collection and secure the exfiltration route through National Street. Aerial attacks were co-ordinated between the seasoned AH-1F Cobras of the QRF’s Task Force 2-25 and 160 SOAR.

By 2210 it seemed things were ready to roll. The convoy would move out by 2300. It had been well over five hours since 10th Mountain Division first responded with Charlie Company. Although some criticism may have been deserved, it should be noted that 10th Mountain did not have armour. They, much like the 75th Ranger Regiment were a light infantry unit and unfamiliar with mechanised units. The Malaysian soldiers had to physically demonstrate the simplest of tasks to the American light infantrymen. Nonetheless, few people appreciated the communications difficulties to not only co-ordinate a plan, but to implement and actually execute it with so many foreign counterparts. Yes, some of the Pakistanis and Malaysians spoke English and yes, the US had liaison officers, but relaying information up and down the several chains of command and receiving at least one change to the original plan from TFR’s TOC only added to the confusion. And, while all plans were forged, there was still the problem of supporting the trapped SOF unit and trying to find out about the unaccounted for personnel at the second (Durant) crash site.

October 3rd. A squad of the QRF moves to a staging area for assembly. Credit: Mark Jackson

There were also cultural problems. US troops are more inclined to fight at night given their technological superiority and their western way of war (I no longer believe in culture-type warfare argued by Keegan back in the day). Their UN counterparts were not as well equipped and not as culturally inclined to close with the enemy (I no longer believe in culture-type warfare argued by Keegan back in the day). The Pakistanis had taken some serious casualties over the past few months. The Malaysians were not too keen to expose their thin-skinned APC’s to accurate and devastating RPG fire. And UN troops had to deal with their own chains of command as well. We can easily see why it took longer to launch the relief than originally anticipated. No matter one’s opinion on the timeliness of the matter, one military truism was, is and will be certain: proper planning prevents piss poor performance. And the Americans certainly had not planned their initial relief efforts well.

As events progressed, the Pakistani higher command demanded a change in the order of movement and the plan. After several sharp exchanges between the Americans and the Pakistani tank commanders, a platoon from A/Co. 2-14, in Condors would lead the charge and the tanks could only advance half way. Credit should be given here to the Pakistani tank commanders as they supported the effort to a greater degree than approved by their higher command.

Bravo Company, 2-14th Infantry remained at the docks at New Port as a possible helicopter reserve.

Finally, at 2323 Hours, about seven hours after the downing of the first Black Hawk the 2-mile long convoy departed. The final task organisation under Lieutenant Colonel Bill David’s command was as follows:

A/Co, 2-14, one Malaysian APC Company, 3rd Platoon from C/Co, 1st Battalion, 87th Infantry and one squad from the 41st Engineers,10th Mountain Division [Crash site 1, North, Wolcott].

C/Co, 2-14, one Malaysian APC Company, one AT Platoon, and one squad from 41st Engineers [Crash site 2, South, Durant].

Additionally, one Pakistani Tank Platoon (four T-55’s), Scout Platoon, 2-14, and a TFR element comprised of Delta, Rangers, Navy SEALs and others [secure holding area and egress route].

This is the shantytown days before it was completely devastated by C/Co, 2-14 after the first failed rescue attempt on October 3rd. Credit: Mark Jackson

The column came under some immediate light attacks but continued its movement. It stretched and collapsed like an accordion. Communication between the various 10th Mountain squads was bad due to several factors. First, the radios could not function properly as the walls of the Condors prevented solid transmission. Secondly, there was no radio communication with the Malaysian drivers, and the subsequent deafening gun battles would require physical contact with the vehicle commanders in order to affect any kind of control. Leaders during the battle would have to bang on the vehicles and direct them on many occasions. Often these efforts proved futile.

At 2350 the Pakistanis stopped as the convoy reached National Street. Ten minutes later and 3/4 of a mile away from their target, the convoy entered Aideed’s area of control and was immediately ambushed but staggered on. Alpha Company’s commander Captain Drew Meyerowich had to cope with two stray Condors. However, the column pressed on, no matter what like an unstoppable juggernaut.

The two isolated vehicles were attacked near the southern crash site. Both Condors were destroyed, resulting in the death and injury of Malaysian soldiers. The squad and an engineer team under Lieutenant Mark Hollis dismounted and blew a hole through a wall to enter the relative safety of a courtyard. This group would eventually be rescued by Charlie Company.

After a Pakistani tank was rocked by seven or eight rocket propelled grenades, the main column was forced to stop yet again and it took some time for an American officer to get the tank to continue its movement. Eventually, the holding area on National Street was secured and the companies separated as planned.

Whetstone’s Charlie Company located the southern site but found nothing there. Thermite grenades were used to destroy the Black Hawk. House-to-house fighting for the next 2 hours, aided by Cobras from 2-25, eventually enabled them to link up with Hollis’ lost patrol and return to UN controlled areas.

Meanwhile, Alpha Company, minus the lost squad of 2ndPlatoon, now in the lead, moved to the first crash site where TFR had also been engaged in severe and chaotic firefights. The white painted Condors were an easy target and hit repeatedly. Some drivers failed to respond when given directions, requiring more time and spreading the units out even further. The massed fire from the Somalis made it difficult to advance in an orderly fashion and the fog of war was thick. Often a Humvee would have to bypass a reluctant Condor and engage targets. The Malaysians were concerned about their lost comrades and not too anxious to get destroyed by RPG fire.

Link-up was conducted at 0155 Hours, October 4th when one of the 10th Mountain troopers spotted TFR’s strobe lights through his AN/PVS 7B night vision. An officer recalls the link-up with clarity:

The situation on the objective was well under control. The TFR soldiers were consolidated in two or three buildings with security. The Special Operations soldiers were understandably tired and short of water and ammunition. They seemed happy to see us, and we were happy to see them as well.

The Pakistani Soccer Stadium in the early morning of October 4th. In the background are the Malaysian Condors so crucial to the final charge. Credit: Mark Jackson

Of course it sounds easier than it was. The firefights, darkness and confusing alleys, the lack of direct communications with anyone at the crash site, required a communication chain from the lead platoon, to their Company Commander to their Battalion TOC, Lt.Col. David, who in turn contacted the isolated special forces through his own TFR liaison officer. Not really the best way to conduct a rather complex link-up between friendly forces at night, while under fire, with units spread over many blocks.

Another factor that bears consideration; the entire time this relief effort was underway, a constant stream of communications bounced back and forth between all parties involved. For example, around 0225 Colonel Gasper ordered the relief column to a Pakistani held stadium instead of withdrawing to the airport. This information needed to be ultimately disseminated to the lowest level.

A close up of the Condor armored personnel carrier. Credit: Mark Jackson

A Medevac flight out of the stadium. The triage area is off to the right. Credit: Mark Jackson

It took many more hours to free the trapped body of one of the pilots at the northern site, all while under sporadic attacks, including Somali mortars. One 10th Mountain officer recalled a helicopter firing at enemy forces and buildings as close as 35 meters from his position, showering them with brass. His honesty is rather remarkable: “I told the officer controlling the air strike to warn us next time. I had never been so close to an air strike, and we were plenty scared. For the next several hours, aircraft continued to fire all around our position 35 to 50 meters from us.”

At 0530 Hours the convoy pulled out, back the way they came, to the BN TOC and casualty collection area on National Street, all the while receiving air support. The convoy snaked throughout the war torn and shredded streets of Mogadishu, forcing some soldiers, including many wounded from TFR, to run alongside the convoy or attempt to catch up.

Exhausted soldiers from 10th Mountain crash on their Humvees. Credit: Mark Jackson

The Somalis knew this was their last chance, and the fighting stiffened once again. Condors and Humvees fired on 2nd and 3rd story buildings, while the grunts were spraying and targeting all alleyways, windows, doors and anything that moved. Many vehicles sped up, isolating more soldiers. In the end, all were accounted for and loaded in or on top of various vehicles. They headed straight for the Pakistani controlled soccer stadium without much order. Cobras destroyed any and all abandoned APC’s.

The mission was a success for the Quick Reaction Force. 10th Mountain Division co-ordinated with UN troops and special operations forces to rescue a trapped American unit in the heartland of a “bad guy.”

The Mountain Division had two soldiers killed in action: Private First Class James Martin and Sergeant Cornell Houston. The Malaysians reported one death. Task Force Ranger suffered 16 fatalities. The Somalis suffered disproportionately; estimates range between 3-400 killed (some estimates went as high as 1000 deaths) with approximately 1000 wounded.

SPC Fullgraff (Right) and SPC Wontkowski (Left) display the uniform and ammo clip of SPC Fullgraff worn during the firefight. According to Fullgraff, a round struck his magazine sending shrapnel into his lower arm, then entered and exited through his upper arm. The 10th MD patch is clearly visible. Credit: Mark Jackson

But the ratio of deaths is completely irrelevant and should never be a measuring stick of success. The initial raid by TFR was successful and the final charge of the 10th Mountain Division saved the day. Moreover, was it really a charge? The omniscient Prussian military warrior-scholar Carl von Clausewitz (1780-1831) was right when he wrote on the friction of war: “everything in war is very simple, but the simplest thing is difficult.” The last charge at Mogadishu then was more or less a slow and inexorable climb to glory. The 10th Mountain Division had stayed true to their motto.

In the war against terrorism, we may find ourselves in similar circumstances. A special operation’s raid against well-trained and highly motivated individuals can easily require the additional manpower of regular troops. The Battle of the Black Sea serves as a reminder to future special operations that they may very well have to depend on those legs to sustain a prolonged encounter. It behoves all to remember that at the end of the day, no matter the status of the units fighting, it is the soldier that must stand his ground and do or die.

1st Platoon, Charlie Company, 41st Engineers, 10th MD

This photo was taken the day before departure from Somalia (16 Dec 1993).

Top to bottom, Left to Right.

1st Row ( 3rd Squad ) SGT Ledesma, PV2 Asbury, PV2 Nunez, PV2 Neil, PV2 Little, SPC Jackson (me), SGT Durrante, SGT McMahon

2nd Row ( 2nd Squad ) SSG Linzan, PV2 Henderson, PV2 Tapscott, PV2 Wilkerson, PFC Dishman, SPC Scarzella, SGT Thiele

3rd Row ( 1st Squad ) SGT McCue, Pv2 Wind, SPC Fullgraff, SPC Wontkowski, PV2 Lea, SGT Hegy, PV2 Franco

4th Row 1LT Nelson, SFC Blaylock

Not Pictured

PV2 Ly - Wounded in action 10/04/94

SSG Maxwell - Wounded in action 10/04/94

SGT Houston - Wounded in action 10/04/94, Died of injuries 10/06/94

SPC Lepre

SPC Rodriguez.

Credit: Mark Jackson

Additional reading:

Bolger, Daniel P., Death Ground: Today’s American Infantry in Battle, Presidio Press, Novato, 1990.

Bowden, Mark, Black Hawk Down: A Story of Modern War, Atlantic Monthly Press, New York, 1999.

Hackworth, David H., Hazardous Duty, William Morrow, New York, 1996.

Clausewitz, Carl von, On War, translated by Michael Howard and Peter Paret, Princeton University Press, New jersey, 1984.

DeLong, Kent and Steven Tuckey, Mogadishu! Heroism and Tragedy, Praeger Publishers, Conneticut, 1994.

Stanton, Martin, Somalia on $5.00 a Day, Presidio Press, Novato, 2001.

Copyright: Mir Bahmanyar/Osprey Publishing